From 15 July 2024 First Community will no longer be accepting referrals to the Long Covid Rehabilitation Service. The service will close on 31 August 2024.

The below guide is available for patients and carers.

What is Long COVID?

Post COVID-19 Syndrome is also called Long COVID. It describes the signs and symptoms that develop during or following an infection consistent with COVID-19, which continues for more than 12 weeks and are not explained by an alternative diagnosis.

The condition usually presents with clusters of symptoms, often overlapping, which may change over time and can affect any system within your body.

The severity of your COVID-19 illness does not indicate whether you will go on to develop Long COVID. In other words, you may have a mild case of COVID-19 and then develop Long COVID, or you may have been severely ill with COVID-19 and then suffer no longer term after effects.

There is a broad spectrum of symptoms that you may or may not experience with Long COVID. The most commonly reported symptoms are listed below:

- Fatigue

- Breathlessness

- Chills and sweats

- A fast heart rate at rest or on exertion

- Headaches • Poor concentration and short-term memory problems

- Voice problems • Muscle weakness

- Pain – back / joint / muscular / chest

- Anxiety

- Dizziness

- Flare up / exacerbation of pre-existing health problems

- Hair loss • Skin rashes

- Tinnitus

- Gastro-intestinal issues

- Loss of taste and smell

- Numbness / pins and needles

- Insomnia

- Hormonal imbalance

The severity and duration of symptoms for people who have COVID-19 can vary. For most people, symptoms last 7-14 days and will be very mild. To manage mild symptoms:

- Stay hydrated

- Take paracetamol if you have a temperature

- Rest

- Get up and move about at regular intervals

Please seek advice from your GP or by calling 111 if you feel your symptoms are not improving and might need further investigation.

What do I do if my symptoms get worse?

There are certain medical complications that can arise while recovering from COVID-19 that require an urgent medical review. Monitor your symptoms regularly and seek medical advice (GP, 111 or 999 as appropriate) if you experience one of the following ‘red flag’ symptoms’:

- You become very short of breath with minimal activity that does not improve with any of the positions of ease for breathlessness

- There is a change in how breathless you are at rest that does not get better by using the breathing control techniques

- You experience chest pain, racing of the heartbeat or dizziness in certain positions or during exercise or activity

- Your confusion is getting worse or you have difficulty speaking or understanding speech

- You have new weakness in your face, arm or leg, especially on one side of the body

- Your anxiety or mood worsens, or you have thoughts of harming yourself.

(REFEREENCE: WHO – Support for rehabilitation: self-management after COVID-19 related illness, 2nd edition)

What causes Long COVID?

At the time of writing there has been no definitive cause to explain why some people get Long COVID and others do not. Research is going on worldwide to try and identify the cause. It is believed that Long COVID can impact the autonomic nervous system due to an increase in numbers of patients with dysautonomia. Dysautonomia is described below.

Understanding the nervous system

Our nervous system is made up of a network of nerves across the whole of our bodies that takes information to and from the brain and spinal cord (the central nervous system). It contains some nerves that carry sensations and instructions that we are consciously aware of and under our control.

The other part of our nervous system is the autonomic nervous system. This controls processes which we are not consciously in control of such as how fast our heart should beat, what blood pressure we should have and when to initiate digestion of food.

The autonomic nervous system has two branches – the sympathetic branch and the parasympathetic branch. The sympathetic nervous system response is also known as the ‘fight or flight response’. The parasympathetic response is also known as the ‘rest and digest’ response. Usually these branches are balanced, with one counteracting the other to bring the body into a state of balance.

Dysautonomia

Dysautonomia refers to these two responses not being in a healthy balance with each other. The fight or flight response is useful for getting us out of short-lived periods of danger. For instance, if you cross a road and a car comes hurtling towards you, your heart rate increases, your reaction time improves and you get out of the way. However, what seems to happen in Long COVID is the ‘fight or flight’ response goes into overdrive. Our bodies are not used to being in this response for a long period of time. This can contribute to many symptoms of Long COVID including fast heart rate, dizziness and dry mouth. Importantly, it is very draining on the body’s energy resources to be in this state for a long time and it can contribute to fatigue.

How is dysautonomia diagnosed and treated?

One way of us knowing if dysautonomia is contributing to your symptoms is by doing a test called the ‘Lean Test’. This will be carried out when you have your initial assessment. It is a test of your heart rate and blood pressure when lying for 2-3 minutes and then on standing whilst leaning against a wall for 10 minutes.

Certain changes in your heart rate and blood pressure during this test are suggestive of dysautonomia. If you have dysautonomia this will be discussed with you along with management strategies. Any activity that relaxes you will be helpful for stimulating the ‘rest and digest’ response and drawing you out of the ‘fight or flight’ response to help bring the body back into balance. This may include mindfulness, meditation, being in nature etc and your rehab team will help you find what works for you.

Your physiotherapist will discuss with you if it is thought you may have symptoms of dysautonomia, and appropriate management strategies will be provided whilst you wait for further cardiac investigations.

The emotional impact of Long COVID

Having COVID-19 can be very frightening. It is understandable that the experience of contracting the virus and then suffering from ongoing symptoms for months afterwards can have a huge emotional impact. Some of the more common emotional problems are outlined below:

- Feeling anxious when struggling to catch your breath and when your heart is racing

- Feeling low in mood and physically sluggish

- Sleeping poorly

- Feeling preoccupied as to whether you will return to your pre-Covid self

- Worries about finances and/or getting back to work

- Loss of identity

- Worries about family or friends becoming ill and suffering

- Worries about feeling like a burden to family and friends

- Frustration that health experts might not always be able to answer all your questions or give ‘concrete’ explanations

- Intrusive memories from when you were first unwell, that might seem to come ‘out of the blue’

- Nightmares

- Feelings of panic with any hospital reminders/medical appointments

- Loss of control.

What can help?

- Speaking to family and friends

- Online Long-Covid support groups

- Relaxation and Meditation

- Light and/or low impact exercise, E.G. walking, Pilates, Yoga, Tai Chi

- Trying to do the activities that you find enjoyable and relaxing

- Taking control e.g. scheduling a manageable week and reflecting on what you have achieved

- Coming to terms with your current self to reduce demoralisation and so you can work with and around your symptoms.

Menopause and Long COVID

Long COVID seems to affect more women than men and particularly in the age group 40-60. This has led researchers to question if there is a link between Long COVID and the menopause. So far it has been felt likely that covid infection could impact the ovaries, reducing hormone production and potentially this could exacerbate the symptoms of menopause. Further research into this area is ongoing.

There are many overlapping symptoms between Long COVID and the menopause. Some of these include ‘brain fog’, poor sleep, headaches, fatigue, joint pains, anxiety and low mood. Menopause in addition can present with hot flushes and disruption to periods. The average age in the UK is 51 but women can have menopausal symptoms prior to this as hormone levels fluctuate (perimenopause).

If you feel that any of your symptoms could be menopausal rather than related to Long COVID alone then please discuss this with your GP. Treatments for menopausal symptoms include lifestyle changes, hormone replacement therapy and there are other medication options too. These can, in some women, have huge benefits to quality of life.

Relaxation

Relaxation is an important part of energy conservation. It can help you to control your anxiety, improve the quality of your sleep, reduce pain and help manage the symptoms of dysautonomia. Below is a technique you can use to manage anxiety and help you relax.

Grounding technique

Take slow gentle breaths and ask yourself:

- What are five things I can see?

- What are four things I can feel?

- What are three things I can hear?

- What are two things I can smell?

- What is one thing I can taste?

Think of the answers slowly to yourself, one sense at a time and spend at least ten seconds focusing on each one.

There are numerous different relaxation techniques you can try and what suits one person will vary from another. The internet is a great resource in which to explore different strategies. Here are a few of the more common techniques and some helpful lifestyle changes:

- Progressive muscle relaxation

- Body scan

- Meditation/ Mindfulness

- Hypnotherapy

- Guided imagery or visualisation

- Alexander technique

- Aromatherapy

- Tai Chi

- Yoga Nidra

- Relaxing music

- Exposure to nature

- CBT techniques

- Healthy eating, staying hydrated

- Turn off devices, limit social media

- Reduce exposure to the news, be wary of disinformation

- Be assertive and set boundaries with people

- De-clutter

- Improving your ability to relax takes regular application

- Do not have expectations when engaging in relaxation/meditation. Try to stay in the moment.

Thinking patterns and symptoms

It is important to remember that your symptoms are a normal part of your recovery following COVID-19.

Fixating on something will often magnify its significance. Worrying and thinking about your symptoms can often make them worse.

For example, if you focus on your elevated breathing pattern for a prolonged period of time, this can result in increased anxiety levels and serve to increase your heart and respiratory rate further. This principle can apply to other Long COVID symptoms. For example, if you focus on your headache, it can result in a more severe one; if you focus on not being able to sleep, this is likely to exacerbate your insomnia; or if you worry about your difficulty with processing what someone is saying to you, it can negatively impact on your concentration.

Before you experienced COVID-19 you may already have had some of these symptoms, therefore treat them in the same way you would have done before. It can be useful to list your symptoms so you can discuss them with your medical team as they may be able help you manage them.

Often symptoms are linked and can set off a chain reaction: the onset of one symptom can lead to another. If you are fatigued your concentration will be affected, this in turn will affect your memory. These lapses of memory can increase your anxiety, which increases your fatigue. This can be described as a ‘vicious cycle’. Working on your symptoms can reduce likelihood of onset, the severity of a symptom and reduce the risk of a chain reaction onset.

During your recovery you will have good days and bad days, ups and downs. This is normal and it is important not to dwell on the ‘bad days’. Record the progress you make and congratulate yourself on ‘small wins’. Learn to ‘take a step back’ and see the bigger picture in relation to your recovery: the small improvements mean something. Throughout your rehabilitation try to be kind to yourself, be wary about being overly critical. Consider what advice you might give to a friend and treat yourself in the same way.

Towards the end of this page, you will find a list of useful online links. These are a fantastic resource to support your wellbeing. The British Lung Foundation has a support line for people who have recovered from COVID-19. Further information can be found at:

- www.blf.org.uk

- NHS England’s website for ‘Your COVID Recovery’ can be found at https://www.yourcovidrecovery.nhs.uk/.

- There are also various social media sites available.

The COVID-19 Rehabilitation Team

Following a referral to the Covid rehab team from your GP or medical professional, you will undergo a telephone initial triage to determine what professional input you need. This could include:

- Physiotherapy: input for mobility, breathlessness, exercise tolerance, group exercise as indicated based on your individual assessment

- Occupational therapy: input for fatigue management, cognitive support, social re-integration, equipment to meet your individual needs

- Speech and language therapy: for swallowing difficulties, word finding and/or cognitive communication difficulties, onward referrals to Voice therapy. Advice and onward referrals for further investigations for gastro-oesophageal reflux.

Referrals can be emailed to: fchc.covidrehab@nhs.net

We look forward to supporting you through your Long Covid recovery.

Breathlessness and Long COVID

Breathlessness and Long COVID Breathlessness is a very common symptom in people with Long COVID. Your lungs can become inflamed with your initial infection and the effort of breathing can increase.

You may be breathing more quickly and shallower than normal, however, it is important to try and stay calm. As your lungs recover and time passes into the 12-week mark following infection, there can be other reasons for your breathlessness to continue. These can be due to:

- Change to your breathing pattern

- Fatigue

- Effects of dysautonomia

- Poor posture

- Muscle weakness

- Anxiety

- Becoming unfit

(Please note that this is not an exhaustive list as research is ongoing into this area).

Other areas of our body can become more tense or work harder when our breathing pattern has changed, or we are breathless. For example, we may start to breathe more from our upper chest, or we may become more tense in our shoulders. This uses much more energy, and the muscles can become tired and sore.

We encourage breathing control to help manage your breathlessness, improve your breathing pattern, help manage anxiety, help regulate your autonomic nervous system, reduce fatigue, and improve posture.

Practice at rest to begin with then use during activity.

There are a number of techniques that you can use when you feel breathless.

Exercises to help manage your breathing

Breathing exercises can help you manage your breathlessness and reduce its impact on your everyday activities. Sit in a comfortable position relaxing your shoulders, either lying or sitting. Place your hands on your tummy. Close your eyes concentrating on your breath.

Breathing control – to help you relax

- Take a slow breath in through your nose (or mouth if you are unable to do this – but work towards trying to breathe through your nose)

- Allow the air to fill up from the bottom of your lungs to the top of your chest

- Try to slow your breathing down. You should feel your tummy move forwards and backwards with each breath.

- Try to breathe in through your nose, for the count of one, then PAUSE

- Breathe out for a count of two through your mouth

- Work towards a longer breath out than in and this will help slow your breathing rate down

- Note areas of tension in your body and try to release this with each breath out

- Gradually try to make your breaths slower.

Breathing control while walking

This will help you walk on the flat, climb stairs and negotiate slopes. Try to keep your shoulders and upper chest relaxed and use your breathing control. Time your breathing with your stepping.

- Breathe in through your nose – 1 step

- Breathe out through your mouth – 1 or 2 steps.

Breathe a rectangle

This is a useful exercise to try when feeling breathless on activity but is beneficial to practice several times of day when relaxed to start and build on from the breathing control.

- Find a comfortable position

- Look for a rectangle shape in the room such as a window, door or TV screen

- Move around the sides of the rectangle with your eyes, breathing in on the short sides and out on the long sides

- Aim to breathe in and out through the nose slowly.

You are aiming towards breathing in for a count of four and breathing out for a count of six, however the main thing to achieve is a longer out breath than in breath. Early indications from research suggest that this helps with many symptoms of dysautonomia, when performed for 10 minutes (minimum of 5 minutes), 2-3 times a day gets the best results, especially if the last session if done before or in bed.

This may also be a useful technique for you to do when you are preparing to do something that you deem likely to be stressful, such as a work meeting, and then also to do this afterwards as a way of supporting recovery. Routine is key, try to build this into your everyday for optimum results.

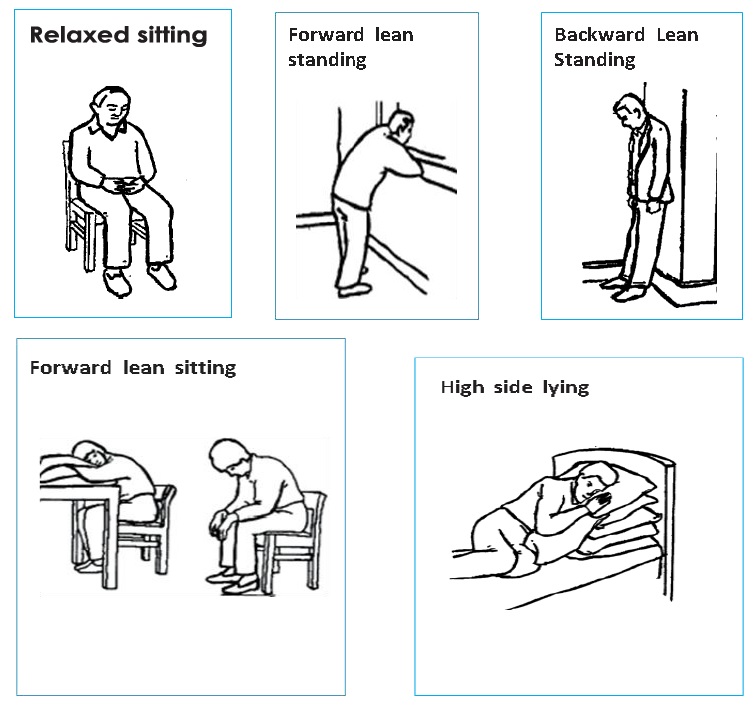

Positions to manage breathlessness

Following COVID-19 you may find you have continued breathlessness. You should monitor this and if it gets worse seek further review from your GP or 111.

These positions can help ease your breathlessness and can be used when resting or when mobilising.

For further information on positions to help ease breathlessness, please refer to the following information online:

How to Cope With Being Short Of Breath – Positions

https://www.acprc.org.uk/publications/patient-information-leaflets/

Pursed lip breathing

Pursed lip breathing can be used at any time to help you control your breathing. This helps to empty all the air out of your lungs in a slow and controlled manner.

- Breathe in gently through your nose

- Then purse your lips as though you’re going to blow out a candle

- Blow out with your lips in this pursed position. Imagine gently blowing out a candle when you breathe out. Blow out only for as long as is comfortable – don’t force your lungs to empty.

Blow as you go

This is useful during activities that make you breathless e.g. lifting an object (can be used with pursed lip breathing):

- Breathe in before you make the effort

- Breathe out whilst making the effort (e.g. as you lift the object)

- Always breathe out on the hardest part of the action.

Managing your cough

A dry, persistent cough is one of the most commonly reported symptoms for COVID-19 and this can be irritating and exhausting and lead to inflammation in the upper airways.

Strategies to manage a dry cough:

- Stay well hydrated

- Sipping a soft drink – take small sips, one after the other, avoid taking large sips

- Steam inhalation – pour hot water into a bowl and put your head over the bowl. If comfortable, cover your head and bowl with a towel. Do not use boiling water with small children to avoid the risk of scalding

- Drink warm honey and lemon or another warm drink, this can help to soothe the throat

- If you do not have a drink to hand, but need to cough, try swallowing repeatedly. This can work in a similar way to sipping water

- If you feel that you must cough then it is better to ‘huff’ than cough. Take in a deep breath and huff out on the ‘h’ sound followed by a gentle cough. Imagine you want to steam up a mirror with your breath. It is quite a forceful action, but very effective. Only carry it out 3 to 4 times in one go as it can make you dizzy.

Stop cough exercise

- As soon as you feel the urge to cough, close your mouth and cover it with your hand (SMOTHER the cough).

- At the same time, make yourself SWALLOW. STOP breathing - take a pause.

- When you start to breathe again, breathe in and out through your nose SOFTLY.

Strategies to manage a productive (wet or chesty) cough:

- Keep well hydrated

- Steam inhalation

- Try lying on either side, as flat as you can. This can help drain the phlegm

- Try moving around, a walk or climbing the stairs. This will help to move the phlegm so that you can cough it out.

Long COVID and Fatigue

Fatigue is the most common debilitating symptom that is experienced in Long COVID. It is often described as an overwhelming sense of tiredness which can be physical, emotional, cognitive, social and spiritual.

Fatigue can impact on all activities of daily living, ranging from your employment, planning and cooking a meal, holding and understanding a conversation, caring responsibilities and social activities such as playing with your children.

Understanding how to get the most out your limited energy reserves is a puzzle which is unique to you. The process of understanding this puzzle in the early stages can take reflection, trial and errors so you can then piece back a life which maximises your limited energy to help enhance your quality of life.

Physical Fatigue

Some people find that when they are fatigued their body feels overwhelmingly heavy and that moving takes an enormous amount of energy. When increasing your levels of activity, you may experience an increase in physical symptoms, e.g. muscular aches and pains. This can be a normal process and may require careful monitoring.

Mental and Cognitive Fatigue

Many people find that when they are fatigued it becomes difficult to think, concentrate or take in new information and consequently memory and learning is affected. Some people find even basic word finding and thinking difficult. Working at the computer, reading a book or delivering a talk are all examples of activities that can cause cognitive fatigue.

People with Long COVID can even feel exhausted after completing the most basic of tasks such as making a cup of tea, and others wake up feeling as tired as they did before they went to sleep.

Fatigue affects people in different ways, and it may change from week to week, day to day or hour to hour. It may also mean people have reduced motivation to do anything because they are so fatigued and know that undertaking the smallest task will leave them exhausted. Fatigue is an ‘invisible disability’ can be difficult to explain to family/friends/colleagues.

Informing and helping others to understand your fatigue and how it impacts on you can make a big difference to how you cope with and manage your fatigue.

From our current knowledge of post viral fatigue and other previous similar viral infections such as SARS, there are some general principles around managing fatigue that can help in supporting the natural recovery process.

Fatigue Management

The initial phase

If you have or have had coronavirus it is likely that you will experience fatigue as a symptom. This is the body’s normal response to dealing with an infection.

For most the infection and initial fatigue will be a mild to moderate with recovery occurring over a week or two. During this initial phase it is important to:

- Sleep – you may find that you need to sleep much more. This is normal during an infection so sleep as much as you feel you need

- Rest – this allows your body to focus on dealing with the infection. In this situation, rest means periods of time during the day doing very little, physically or mentally. Even lowlevel activity such as TV or reading may need to be paced or minimised, depending on your level of illness

- Eat and hydrate – eat and drink little and often if you can, increase your fluid intake if your appetite is low, sipping water regularly throughout the day

- Move – If you feel well enough, move at regular intervals throughout the day to keep your body and circulation moving. This could be simple stretches either in your bed or chair if you are unable to walk around

- Pause your work/education - allow yourself to fully recover from the initial infection before returning to your previous activity levels.

The recovery phase

When people start to feel better after an infection, it is often tempting to return to previous levels of work, leisure and social activities.

However, if fatigue and other symptoms are continuing it can be important to do this slowly and gently. Don’t try to ‘push through’ what you feel you can manage easily.

The most important aspect of managing post infection fatigue is giving yourself time for recuperation, or convalescence as it has been known. This requires a combination of rest, relaxation and gentle activity.

In practice this involves

- Activity Management – balancing periods of low- level gentle activity with periods of rest. You could start with some light activity or tasks followed by longer periods of rest. Mix up the physical and mental activities throughout the day

- Setting the limits – Finding the right balance of activity management is very individual to you and the stage that you are at with your recovery. Once you’ve worked out what is a suitable level and duration to do an activity try to set the limit before you start something and do not exceed this i.e. unload just the top layer of the dishwasher or check through emails for 5 minutes

- Routine – Try to resume a pattern of sleep, mealtimes and activity. Avoid doing too much on a good day, that then might exacerbate the fatigue and other symptoms. Having a basic routine, that has some flexibility, can be helpful for when you are ready to start increasing. A regular routine can also help you sleep better

- Rest – Your body will continue to need rest to help with healing and recovery. You may find that you do not need to rest for long periods like you did initially, but regular short rests throughout the day will continue to be helpful. Take as much rest as you need

- Relaxation/meditation – adding in approaches such as mindfulness or relaxation/breathing techniques can help to aid restorative rest. There are some useful resources online

- Sleep – Whilst we encourage resuming a routine for sleep, sleeping for longer can often be an important requirement for ongoing healing following an acute infection. You may find in this phase a short day-time nap, 30 – 45 minutes, not too late in the afternoon is helpful

- Diet – Maintaining a healthy diet with regular fluid intake will help to improve your energy levels. If possible, avoid caffeine and alcohol as much as you can

- Mental wellbeing – Looking after your emotional health is another important factor in managing fatigue. We know that stress and anxiety can drain the energy battery very quickly. We know that fun and pleasurable activity can help both well-being and energy levels so build these into your activity plan. This can be something small, such as chatting to a friend or watching your favourite TV show

- Work/education - It might be advisable to avoid going back too soon to work once the initial viral symptoms of fever or cough have subsided and to give yourself a little time to recover. You may find a phased or gradual return helpful, for example, starting with just mornings every other day and slowly building up over the next few weeks. You may be able to get support from occupational health or a ‘fit note’ from your GP

- Exercise – Depending on the stage of your recovery, some exercise may be helpful. This might be some gentle stretches or yoga or a short walk. For people who usually do a lot of exercise, it is important to only do a small fraction of what you would normally do and at a gentle pace. Resume slowly and gradually increase over time as your illness improves.

Post infection

You may be starting to feel better after a few weeks and over time you may feel able to increase your activity gradually. Resist pushing through the fatigue and maintain some degree of routine, rest and activity. In most cases people do eventually recover from postviral fatigue after a period of convalescence, but it can sometimes take many months.

However, if your health is not improving, or if you continue to experience persistent symptoms after a few months that interfere with your capacity to carry out normal everyday activities, it is advisable to speak with your GP.

They can check to find out if there are any other causes for the fatigue.

Fatigue can sometimes have other causes such as anaemia or thyroid function and, in a small number of cases, viral infections can sometimes trigger serious chronic, long-term illnesses such as Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME) or Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS).

Energy Conservation

As you recover you are likely to find that your energy levels fluctuate from day to day.

Walking around your home might be difficult, including managing the stairs, accessing toileting facilities and managing your daily routine. This may result in you needing to adapt the activities that you do to enable you to conserve your energy.

Whilst you recover, you may need:

- To consider a different set up such as single level living either downstairs or upstairs whilst you recover

- Specialist equipment to make things easier.

With this analogy in mind, it may be useful to keep a note of how tiring different activities are for you in order to help you understand the pattern of your fatigue and enable you to manage and adapt to this better.

Boom and Bust Pattern

People tend to use their symptoms to decide how much they do. So on ‘good days’ they may try to do more, often trying to ‘catch up’ and very often then overdo it. This can then result in experiencing a bad day and some people describe this as a ‘relapse’ when they might experience more symptoms, feel low and are able to do very little.

It is important to remember that all activity takes energy, whether it is physical, mental or emotional.

You might have noticed that when you ‘overdo’ things, your symptoms are worse, and you need to rest more. Resting decreases the symptoms and you are tempted to be active again. This is called the ‘boom and bust pattern’ and is detrimental to your recovery.

Conserving your energy using the ‘four Ps’

Planning

Planning includes organising daily routines to allow completion of essential activities when you have the most energy. For example, many find it more helpful to perform strenuous tasks such as dressing early in the day when strength and stamina are often at their peak. It is important to think about the task prior to performing the task and expending physical energy.

Consider the following:

- Think about the steps that need to be completed and items required for the task.

- Prepare the required items ahead of time.

- Keep frequently used items in easily accessible places.

- Have duplicate items available to limit unnecessary trips between the bathroom, bedroom, or kitchen.

- Consider using a bag, basket, or rolling trolley to carry tools or supplies in one trip.

- Consider your weekly routine. It will be beneficial to schedule strenuous activities, such as going to the hairdresser, attending religious services, and shopping, evenly throughout the week instead of all in one day.

Pacing

Pacing is a strategy that helps you to get out of this boom and bust cycle and helps you to manage your activities without aggravating your symptoms.

You should develop an activity plan which allows you to stay within your current ‘energy envelope’ and therefore avoid ‘overdoing things’. Your levels of activity can then be increased in a controlled way over time as your stamina increases.

Consider the following:

- Allow plenty of time to complete activities and incorporate frequent rests.

- Perform tasks at a moderate rate and avoid rushing. Although a task may be completed in less time, rushing utilises more energy and leaves less ‘in the bank’ for later activities.

- Allow plenty of time for rest and relaxation. Take a morning or afternoon nap prior to activities or outings to build up energy.

- Breathe easily and properly during activities. Using these techniques helps decrease shortness of breath.

- Rethink activities with rest in mind. For example, sit instead of stand while folding clothes or preparing food. Instead of writing 25 holiday cards in one day consider writing five cards per day over five days.

- Do not ‘overdo’ activity on good days to then avoid the severity of symptoms on bad days, making it easier to predict the level of activity you will be able to achieve on any given day.

- The first step is to think about how much activity you are able to carry out at the moment, even on a ‘not so good’ day. It is important not to compare yourself to others or to how much you could do before. From this, you will be able to set a baseline of activity. This is the amount of activity you will carry out every day.

Prioritising

The third strategy is often the most challenging. When faced with limited energy reserves individuals must look critically at work, family, and social roles and keep only those roles that are necessary and pleasurable.

Prioritising activities is very individual and what may be a priority for some may not be for others. For example, it may be important for someone to use their energy to have a shower each morning and for someone else, they may limit this to three times a week to ensure they save their energy to carry out a leisure task that is important to them.

Consider the following:

- Can a friend or family member assist with chores e.g. emptying the rubbish, vacuuming so you have more energy for necessary and pleasurable tasks?

- Eliminate unnecessary tasks, chores or steps of an activity. Look for shortcuts and loosen the rules

- Be flexible in daily routines enables you to enjoy activities you would lely otherwise miss because of fatigue.

Positioning

Positioning is extremely effective, but not often considered when addressing energy conservation. Current methods of performing tasks may be using more energy than required.

Consider the following:

- Storing items at a convenient height to avoid excessive and prolonged stooping and stretching

- Make sure all work surfaces are at the correct height. If a counter is too short, slouching and bending can occur which results in more energy expenditure

- Use long-handled devices such as reachers or telescope cleaning tools to avoid unnecessary bending and reaching

- Facilitate bathing - use a shower seat and a hand-held shower head.

For further information on fatigue management please refer to the Royal College of Occupational Therapists guidelines online. It can be found by following the below link:

https://www.rcot.co.uk/how-manage-post-viral-fatigue-after-covid-19-0

Top tips for anxiety and panic attacks

If you experience panic attacks or anxiety, try some of the tips below. They can help you to manage stresses in your life and help manage panic and anxiety, so you feel more in control.

Challenge yourself

Some situations can make us feel anxious. In order to work through this we need to expose ourselves to the situation that is making us feel anxious. Try and break this down into smaller stages that you can achieve, practice and build on. The more exposure you have to the situation the less likely it will affect you. Mastery of this will allow you to work through the anxiety so it is no longer problematic.

Breathing exercises

First relax your shoulders and stomach muscles. As you breathe in, allow your stomach to rise and not your chest. Then breathe out slowly, so your stomach falls. Repeat until you feel calm. This technique may take a lot of practice so keep working on it. This technique works well if you are experiencing a panic attack.

Distract your thoughts

Try counting backwards from 100 in 3s. Alternatively keep something on you that comforts you, such as a picture of happy memories. Draw your attention to reliving that memory and how this made you feel. Focus on this until you feel calm.

Think positively

Use positive statements such as ‘I am in control’, ‘I can do this’, ‘Life is great’. Say these statements out loud on a regular basis. The more you hear this, the more you believe it and the more you will feel it!

Talk to someone

Sharing your concerns with someone you can trust can help relieve your anxieties. A problem shared is a problem halved! Talking to others may help you find a solution or offer a different way of looking at the situation.

Practice relaxation techniques

Start by gently breathing in through your nose and out through your mouth, keeping the pace slow and regular. Slowly tense, and then relax all the muscles in your body, starting at your head and working down to your toes. Afterwards, take some time to focus on how your body feels.

Everyone experiences anxiety from time to time. If your anxiety persists for 2 weeks or more, or it is significantly impacting on your daily activities, you will need to see your GP.

Further information

If you would like further information on managing anxiety, panic and stress please email

mindmatters.surrey@sabp.nhs.uk

A wide range of services, support and self-help material can be found on this website.

If you would like Face to Face support, you can self-refer to one of the following:

Think Action Surrey 01737 225370

Think Action Surrey is an experienced provider of high quality, wide range of psychological therapies in Surrey at various locations and times.

Mind Matters 0300 330 5450

Mind Matters provide talking therapies to adults (18+) registered with a GP in Surrey who are experiencing common mental health problems such as depression, anxiety and stress. We provide quick and easy access to our talking therapies, in line with individual needs and best practice.

Online talking therapy 01954 230 066 or visit www.iesohealth.com/surrey

IESO Online talking therapy is provided in partnership with the NHS. Cognitive Behavioural Therapy is delivered online in real time using typed conversation. You meet with an accredited therapist in a secure online therapy room, at a scheduled time and location that is convenient to you. All that is required is access to the internet. Online talking therapy is suitable for those experiencing common mental health problems.

Mood Gym which can be accessed online at: moodgym.com.au

This offers an interactive self-help book which helps you to learn and practise skills which can help to prevent and manage symptoms of depression and anxiety.

Managing Stress - If you would like further information on managing this please visit http://www.mind.org.uk/information-support/tips-for-everyday-living/str….

This explains what stress is, including possible causes, and how you can learn to cope, with tips on how to relax.

If you would like more information about relaxation please visit www.mind.org.uk/information-support/tips-for-everyday-living/relaxation…

This website offers additional tips and techniques on relaxation to try.

Apps

If you would like further support on relaxation, the following apps are free to download and use at your convenience:

Calm: Meditation to relax, focus and sleep better

Calm is the #1 app for mindfulness and meditation to bring more clarity, joy and peace to your daily life. Join the millions experiencing less anxiety and better sleep with the guided meditations, breathing programmes and sleep stories. Recommended by top psychologists and mental health experts to help you to de-stress.

Stop Breathe & Think

Stop Breathe & Think is an award-winning meditation and mindfulness app which helps you to find peace anywhere. It allows you to check in with your emotions, and recommends short, guided meditations, yoga and acupressure videos, tuned to how you feel.

Visible App

An app that monitors energy levels and provides a lot of information to help you with pacing yourself and planning your days.

Additional resources

mindmatters.surrey@sabp.nhs.uk and www.mind.org.uk/information-support/tips-for-everyday-living/relaxation - A wide range of services, support and self-help material can be found on this website.

IAPT website - www.nhs.uk/service-search/find-a-psychological-therapies-service/

This is a self-refer psychological therapy service, without seeing your GP. They offer therapies, such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), for common problems including stress, anxiety, depression and phobias. Once you have referred yourself the service will contact you and you’ll be recommended a therapy.

The therapy you are offered will depend on the problems you are experiencing and how severe they are. The service will also tell you how long you'll wait for your first therapy session. There are different types of psychological therapies available, including online therapy programmes, but they all involve working with a trained therapist.

Managing your diet

Many people experience loss of appetite and reduced food intake when unwell with COVID and during their recovery. It is important to try and eat well and keep hydrated to aid your recovery.

What makes food & drink important?

Eating well is important as your body needs energy, protein, vitamins and minerals to help you fight infections and when recovering. Having a good intake of protein and energy rich foods supports you with rebuilding muscles, maintaining your immune system and increasing your energy levels to allow you to do your usual activities.

What can you do to make the most of your food & drink?

Use the information in the following sections to help ensure you are maintaining good nutrition and hydration and minimising any weight loss:

- ‘Eating for Health’ – if you are a normal weight or overweight and have a good appetite

- ‘Food First advice’ – if you are underweight, losing weight unintentionally or have no appetite

- ‘Side Effects and Symptoms of COVID-19’ – if you are struggling with ongoing effects of COVID-19 which are affecting your intake

- ‘Accessing Food’ – if you are not able to access food as easily as normal

More information can be found on the British Dietitian Association website, where you can access a number of Food Fact Sheets:

https://www.bda.uk.com/resource/long-covid-and-diet.html

1. Eating for Health

A good diet is important for good health. ‘Eating for Health’ means including foods from all the food groups in your diet, and reducing your fat, salt and sugar intake. It is important to eat a wide variety of foods and continue to enjoy your food.

The Eatwell Guide shows how much of what we eat overall should come from each food group to achieve a healthy, balanced diet. You do not need to achieve this balance with every meal but try to get the balance right over a day or even a week.

If you are a normal weight or overweight and have a good appetite, you should have a varied diet and try to include foods from each food group: https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/eat-well/food-guidelines-and-food-labels/t…

Starchy foods (yellow section) are the body’s main source of energy; aim to eat 2 portions at each meal and try to choose wholegrain varieties. Examples of a portion include:

- Rice & Pasta - 2-3 tablespoons (cooked)

- Potato - 2 egg sized

- Bread - 1 medium slice from a large loaf

- Breakfast cereal - 2-3 tablespoons (unsweetened)

Protein foods (pink section) are needed for growth and repair; eat 2-3 portions a day, choosing lean meats and avoiding processed meat. Examples of a portion include:

- Meat & Poultry - 80g (cooked weight) the size of a pack of cards

- White & Oily Fish - 140g (cooked weight) the size of a slim glasses case

- Soya, Tofu & Quorn® - 120g (the size of a snooker ball)

- Pulses (peas, beans & lentils) - 3-4 heaped tablespoons

- Eggs – 2 eggs

Dairy and alternatives (blue section) are rich in calcium and high in protein; aim to have 2-3 portions per day, opting for low fat and unsweetened varieties. Examples of a portion include:

- Cheese – 30g (the size of a small matchbox)

- Yoghurt and Fromage Frais – 1 small pot approx. 150g (e.g. low fat, plain yoghurt)

- Milk – 1 glass approx. 200mls (e.g. skimmed milk)

Fruit and Vegetables (green section) are good sources of vitamins, minerals and fibre; eat at least 5 portions per day and make sure it is a mix of fruit and vegetables or salad. All fresh, tinned, dried and frozen fruits and vegetables count. A portion is around 80g or a handful.

Keep hydrated

The amount of water you drink has a direct effect on your health and wellbeing.

Adults should aim to have between 1600ml-2000ml fluid per day, but this can vary depending on factors such as temperature and activity levels.

Try to choose water, low-fat milk and sugar free drinks. Tea and coffee also count towards your fluid intake but if you drink a lot of these you should be aware of the amount of caffeine you are consuming.

Vitamin D

Vitamin D helps your body to absorb calcium and keep your bones, muscles and teeth healthy. It’s found in oily fish, eggs, meat, milk, margarine and fortified breakfast cereals and yoghurts.

It’s difficult to get all the vitamin D your body needs from food alone. This is because your body makes most of its vitamin D from sunlight during the summer months.

Current guidelines advise those over the age of 65 to take 10 micrograms of Vitamin D each day as a supplement, and all adults should consider taking a supplement during the autumn and winter months. You should also consider taking a vitamin D supplement if you’re indoors for most of the day.

You can buy a vitamin D supplement from most pharmacies and supermarkets. A supplement only needs to contain 10 micrograms to meet the recommendation.

2. Food First Advice

Eating little and often when you have a poor appetite, or have lost weight, can improve your intake of energy, protein, vitamins and minerals. Unintentional weight loss can slow down recovery.

The ‘Food First’ approach may help to increase your intake and prevent further weight loss.

This includes 3 daily goals:

- Aim to have 1 pint of fortified whole milk per day

- Include 2 nourishing snacks or drinks a day

- Have 3 fortified meals every day

You may have also lost some muscle mass during your illness. Try to have 2-3 portions of protein every day to help recover your strength. Examples of a portion size can be found in the ‘Eating for Health’ section.

Fortified Milk

Ensure all the milk you have is whole milk. This can be fresh, long-life or UHT milk.

Fortify it by mixing 4 tablespoons of skimmed milk powder into 1 pint (568 mls) of whole milk. Mix the powder with a small amount of milk first to make a paste, then add the remaining milk, stirring continuously. Once made up, keep it in the fridge to use throughout the day, for example in drinks, on cereal or when cooking.

Nourishing drinks and snacks

Try to have at least 2 nourishing drinks or snacks per day, between meals or in the evening. Adopting a ‘little and often’ eating pattern by having small, nourishing meals, snacks and drinks every two to three hours can really help to increase your intake.

Why not try some of these snack ideas?

Sweet snack ideas*

- Thick & creamy yogurt

- Scone with clotted cream & jam

- Tinned fruit with ice-cream or cream

- Teacake or hot cross bun

- Buttered fruit loaf or malt loaf

- Chocolate or fruit mousse

- Chocolate biscuits

- Crème caramel

- Custard / jam tart

- Milk pudding

- Muesli bar or flapjack

- Jelly and ice cream.

Savoury snack ideas

- Cheese and crackers

- Crackers and dip

- Crumpets with butter

- Crisps

- Nuts

- Savoury scone with butter

- Sandwiches

- Toast with peanut butter or other nut butter

- Mini scotch eggs

- Houmous and bread sticks

- French toast / eggy bread

- Savoury pastry/ pasty

Homemade nourishing drink ideas:

Milkshake*

Ingredients: 200mls whole milk 1 scoop of ice cream 2 tbsp skimmed milk powder 3 tsp vitamin fortified milkshake powder, such as Nesquik or Tesco Milkshake Mix

Method: Add all the ingredients together and whisk. Serve chilled or warm. Calories: 399 Protein: 19.9g

Juice*

Ingredients: 100mls fresh or long-life fruit juice 100mls lemonade 1 scoop ice cream 1 tbsp sugar Method: Mix all the ingredients together. Serve chilled. Calories: 192 Protein: 2.3g

Soup

Ingredients: 1 instant soup sachet 200ml full fat milk 2 tbsp skimmed milk powder Method: Warm the milk. Gradually add the soup sachet and milk powder, stirring well. Calories: 351 Protein:19g

Readymade milkshakes,* drinks and smoothies, such as Frijj®, Mars® or Yazoo®, are available in most supermarkets and convenience stores. You could include these in your diet as a nourishing drink too!

Or how about a hot chocolate, milky coffee or malted drink, such as Ovaltine® or Horlicks®, made with fortified milk?

You may also be prescribed nutritional supplement drinks; these provide additional calories, protein, vitamins and minerals when you are struggling to meet your needs from food alone.

They are intended to be used to supplement normal food, not as meal replacements, and should be taken as prescribed like any other medicines. In addition to your prescribed nutritional supplements, it is important to ensure that you follow the ‘Food First’ advice on this leaflet.

Fortify your meals

If you are only able to eat small portions of meals, these can be made more nourishing by adding high energy foods to them. This will mean you are getting more energy from your food without struggling to eat a larger meal. You can add these things to homemade meals and convenience foods such as ready meals, tinned foods and frozen meals.

Make every mouthful count!

How to fortify your food:

- Add cream to cereals, porridge, sauces, soups, mashed potato and puddings.

- Add evaporated milk to sauces, custard, jellies, tinned fruit, puddings and coffee.

- Add cheese to mashed potato, soups, sauces, baked beans, scrambled egg and vegetables. Cream cheese and cheese spreads are good for crackers and on toast.

- Add butter or margarine to potatoes, vegetables, soups, pasta. Use thickly on bread.

- Use sugar or honey* in drinks, on cereals and in pudding.

- Add jam or golden syrup* to puddings, yoghurts, porridge.

- Add salad dressings or mayonnaise to salads.

- Non-dairy options could include nut butters, plant-based milks or yoghurts, coconut cream or Oatly™ cream alternative and dairy-free cheese.

*If you have diabetes, continue to choose sugar free drinks, you can have a moderate amount of sugar containing foods. You may also need to monitor your blood sugar levels more closely than normal. Contact your GP or nurse if you have any concerns.

3. Side effects and Symptoms of COVID-19

If you are struggling with ongoing side effects and symptoms of COVID-19, which are limiting your intake, the following tips might help rejuvenate your appetite and desire for food whilst helping you to stop losing further weight.

I have lost my sense of smell and taste

- Try to make your food look as appetising as possible

- Use strong seasonings, herbs and spices such as pepper, cumin or rosemary to flavour your cooking.

- Sharp-tasting foods can be more refreshing, such as fruit and fruit juice

- Cold foods may taste better than hot foods

- Don’t wait until you are hungry to eat. If you have lost your appetite, think of eating as a necessary part of your recovery and treatment.

I have a sore throat

- Drink plenty of fluids

- Try milk or milk-based drinks, such as malted drinks, milkshakes and hot chocolate

- Cold foods may be more soothing, try ice-cream or soft milk jellies

- Avoid rough-textured foods like toast or raw vegetables

- Keep your food moist by adding sauces and gravies

- A homemade honey and lemon drink may be soothing; mix 1-2 teaspoons of honey with lemon juice and boiling water.

I don’t have any energy to eat

- Try using convenience foods such as frozen meals, tinned foods and ready meals

- If you really don’t want to eat, try a nourishing drink. You can make one of the recipes above using fortified milk

- You may find softer foods easier to chew and swallow, such as porridge, scrambled egg, Shepherd’s pie, fish pie, macaroni cheese, baked potatoes (avoiding the skin), or sponge cake with custard

- It may be easier to eat smaller meals more often throughout the day rather than a few bigger meals

- Local meal delivery services may be useful.

I have loose bowels/ diarrhoea

- Ensure you are having a good fluid intake to replace the fluid you are losing

- Limit caffeine intake from tea, coffee and soft drinks

- Try reducing whole-wheat breakfast cereals and breads, choosing white versions instead

- Eat less fibre (for example cereals, raw fruits and vegetables) until the diarrhoea improves

- Eat small, frequent meals made from light foods, for example white fish, poultry, well-cooked eggs, white bread, pasta or rice

- Avoid greasy, fatty foods such as chips and beef burgers, and highly spiced foods.

I feel sick

- Eat ‘little and often’, choosing small meals and snacks more regularly during the day

- Avoid drinking whilst eating; try having drinks between meals instead

- Avoid cooking smells where possible

- Try foods containing ginger such as ginger biscuits, ginger ale or ginger tea

- Avoid letting your stomach get too empty or overloaded

- Keep your mouth and teeth clean

- Try dry meals, for example with less/no sauce or gravy

- Try salty or sharp tasting foods, for example crisps or cheesy biscuits

- Avoid eating too near to bedtime

- Nibble a dry biscuit or dry toast before getting out of bed, especially if your nausea is worse in the mornings.

4. Accessing Food

Self-isolation, particularly for older adults, may mean you are not able to access food as easily as normal. The following information includes helpful hints to try and ensure you have adequate access to food:

- Take advantage of shopping hours set aside for vulnerable and older people.

- Register through the https://www.gov.uk/coronavirus-extremely-vulnerable if you have ask for help getting deliveries of essential supplies like food.

- Ask a friend or neighbour who may be able to help with your shopping.

- Contact Age UK who can deliver meals, groceries and essential medication to your doorstep (Contact telephone numbers - Surrey: 01483 503414, Sussex: 01903 731800)

- Can you access a meals at home delivery service, such as Meals on Wheels, Wiltshire Farm Foods or Oakhouse Foods?

It’s useful to have a store of basic foods if you can’t get to the shops regularly; the list below provides some simple store cupboard and freezer suggestions:

Meat, Fish and alternatives

- Canned meat or fish

- Chickpeas, lentils, beans/ baked beans

- Packets of tofu

- Frozen meat, Quorn and fish

- Fish fingers, breaded fish & chicken

- Samosas, pakoras, falafel

- Ready meals

Milk, Dairy and alternatives

- Long-life, dried, evaporated or condensed milk

- Cans, packets or pots of milk pudding

- Cheese in squeezable tubes

- Ice cream, frozen yoghurt

Cereal and Starchy foods

- Breakfast cereals, porridge, breakfast drinks

- Crisp bread, flatbread, crackers, oatcakes

- Pasta, rice, spaghetti

- Instant mash or canned potatoes

- Frozen chips, mashed potato and baked potatoes

- Freeze bread, rolls, bagels, chapattis, naan bread

Fruit and Vegetables

- Tinned fruit and vegetables, such as tomatoes, sweetcorn, peaches

- Packets and pots of fruit including dried fruit

- Frozen fruit and vegetables

Drinks and other

- Drinking chocolate and malted milk drinks such as Horlicks and Ovaltine

- Long life fruit juice

- Rich fruit loaf, tinned sponge pudding

- Peanut butter

- Cans, jars and dried soups and sauces

- Herbs and spices

- Sugar

- Frozen desserts

If you are concerned that you are continuing to lose weight or struggling with your appetite, ask one of the team to refer you to a Dietitian.

Voice and Swallowing Problems

Breathing and swallowing share a common pathway, this is the mouth, throat and voice box. Shortness of breath and respiratory problems can lead to poor co-ordination in swallowing, resulting in food entering the airway and ‘going down the wrong way’.

Following or during COVID-19 you may experience problems with your swallowing. This can impact on your eating and drinking as well as management of your saliva.

Common signs of difficulty

- Repeated chest infections

- Choking or coughing during or after eating or drinking

- Difficulties with chewing foods or a feeling of something stuck in the throat

- A wet or gurgly voice after eating and drinking

- Prolonged mealtimes

- Food/drink spilling from the nose or mouth

- Pain on swallowing

- Losing weight unintentionally

- Difficulties managing saliva

Physical weakness due to loss of muscle mass during illness has been seen in COVID-19 patients and can impact your ability to feed yourself, chew or safely swallow food, drink and saliva. Following COVID-19 you may additionally experience:

- Tiredness during mealtimes and general fatigue

- Changes to taste and sense of smell

These problems may take some time to recover and should be supported by a Speech and Language Therapist.

We may recommend you change the foods you are eating or the consistency of your drinks to support safe eating and drinking. We can discuss managing excess /not enough saliva with you and your GP.

Problems with swallowing can also be associated with dehydration and malnutrition so it is really important to inform your family/GP so a referral can be made for swallowing assessment.

If the changes to swallowing are significant, you may need to have short/long term supplementary tube feeding to support recovery.

Swallowing difficulties may be persistent if long term respiratory support is needed e.g. oxygen therapy or ventilation.

This may also make you more vulnerable to further chest infections. Other changes to respiratory function post-COVID can include chronic cough.

Things you can try to help with safe swallowing

- Sit as upright as possible for eating and drinking

- Take your time and focus on eating and drinking e.g. turn off the TV

- Eat slowly and take small mouthfuls.

- Choose easy to chew foods and add sauces to reduce fatigue and shortness of breath.

- Small sips, no gulping.

- Avoid eating and drinking when you are short of breath. Ideally you want to be breathing through your nose.

- Eat little and often, resting as required.

- Do not talk when eating.

- Avoid straws, sports bottle lids or cups with lids unless otherwise advised

- Ensure any dentures fit correctly

- Keep your mouth clean with regular teeth brushing and good oral hygiene

- If you use oxygen use nasal prongs whilst eating.

A dry mouth can be a common complaint with people who have respiratory problems. It can result from breathing through your mouth, some medications and the use of oxygen. Not only can a dry mouth be uncomfortable, it can cause swallowing and denture problems along with affecting the taste of food.

Tips to avoid a dry mouth

- Sip water throughout the day.

- Saliva substitute if needed.

- Suck sugar free sweets of chewing gum.

- Apply lip balm.

- Reduce alcohol and caffeine intake.

- Regular dental check ups

- Medication review with your GP

Changes in voice quality

As a result of the COVID-19 virus you may experience some changes to the sound of your voice, and to your comfort and effort levels when using it.

These changes are similar to changes you would expect to experience with a cold or 'flu’ but are expected to be more intense and longer lasting. We anticipate that these voice problems may take 6 – 8 weeks to gradually resolve.

During the illness you are likely to have been coughing excessively for prolonged periods. This brings your vocal cords forcefully together and can leave them swollen and inflamed.

This makes them less able to vibrate freely so the sound of voice changes. Your voice may sound rough or weak and can be very effortful to produce.

You may experience changes in your voice quality. Below are some examples:

- Oedema (swelling) and ulceration of the vocal cords

- Vocal fold palsy

- Acute and long-term impaired voice quality e.g. weakness, hoarseness, vocal fatigue, reduced pitch and volume control

- Raspiness

- Severe dryness of the throat

- Lump in the throat

- Excessive mucous at the back of the throat.

- Voice fatigue after a period of time speaking

Things you can try to look after your voice

- Keep well hydrated. Drink 1½ - 2 litres (4-5 pints) of fluid each day, unless advised otherwise by your GP. Avoid caffeine and alcohol

- Try gentle steaming with hot water (nothing added to it). Breathe in and out gently through your nose or mouth. The steam should not be so hot that it brings on coughing

- Avoid persistent, deliberate throat clearing if you can and, if you can’t prevent it, make it as gentle as possible. Taking small sips of cold water can help to supress the urge to cough

- Chew sugar free gum or suck sugar free sweets/lozenges to promote saliva flow to lubricate the throat and reduce throat clearing. Avoid medicated lozenges and gargles, as these can contain ingredients that may irritate the lining of the throat

- Avoid smoking or vaping

- Talk for short periods at a time. Stop and take a break if your voice feels tired

- Always aim to use your normal voice. Don’t worry if all that comes out is a whisper or a croak; just avoid straining to force the voice to sound louder

- Don’t choose to whisper; this does not ‘save’ the voice; it puts the voice box under strain

- Avoid attempting to talk over background noise such as music, television or car engine noise, as this causes you to try to raise the volume, which can be damaging

- If you are experiencing reflux, speak to your GP as this can further irritate the throat

- Reduce risk of reflux by sitting upright for about 30 minutes after a meal and eating little and often.

Cognition

Cognition means someone’s ‘thinking skills’. People can experience a range of difficulties with their thinking skills post-COVID-19 affecting memory, attention, information processing, planning and organisation.

A common symptom experienced is Brain Fog. Brain Fog is a term used to explain a number of symptoms that affect someone’s ability to think. This involves feeling confused, disorganised, having memory problems, finding it hard to focus and having slower processing of information.

Brain Fog is often made worse by fatigue, meaning the more tired a person is, the more they notice increased difficulty with their thinking skills.

To support your thinking skills, consider the following:

- Minimise distractions: Try to work in a quiet environment with no background distractions. You may find it helpful to, wear ear plugs to let people know that they should try not to interrupt you; If you are distracted when reading text, block off parts of the text using paper, or use your finger as a marker.

- Complete activities when less fatigued: When completing a task that demands your thinking skills, plan this for a time when you are less tired. For example, if you tire as the day goes on - then do the task in the morning.

- Say things out loud: By saying things out loud like ‘what should I be doing now?’ or ‘Stay focused’ or by reading instructions out loud you can help yourself to stay on the right track.

- Take frequent breaks: If the problem is made worse by fatigue, work for shorter periods of time and take breaks. Use ‘little and often’ as a guide and pace yourself.

- Set yourself targets or goals: Having something definite to work towards will help you stay motivated. Setting deadlines like “I’ll do that task at 10 o’clock”, instead of “I’ll do my work later on”.

- Best time and apply structure: Work out when your best time of day is for doing this kind of work. Try to set up your daily/weekly schedule to take account of this. It may help to plan activities ahead of time. Establishing a daily and weekly routine can also help. Keeping a record, or breaking things down into manageable parts can help, so then if you get distracted you can pick up where you left off.

- Use incentives: When you achieve a target or goal, reward yourself, try something very simple such as a cup of tea or coffee, letting yourself watch a TV programme or going for a walk.

- One thing at a time: Concentrate on one thing at a time, do not try to take in too much information at once, as this can lead to mistakes. Do one task then move on to the next.

- Don’t rush things: You may find that you have a tendency to rush everyday tasks and end up making mistakes. Take your time and pace yourself.

- Self-monitor or check and double check your work: Do this with everything you do. It will be slow and hard at first, but it will become a habit as you get accustomed to it. This is the only sure-fire way of picking up on your own errors.

- Gain control: If in everyday conversation you feel you are being ‘overloaded’ and you cannot attend to all the information, ask the person who is talking to you to slow down or repeat themselves. Be assertive and say something like “Excuse me, I think you have lost me, could you repeat that please?”

- Aids: Using lists, post it notes, diaries and calendars can all help support your memory and routine.

Changes to communication

Emerging evidence suggests a proportion of people with COVID-19 also present with changes to communication associated with neurological impairments. You may experience:

- Agitation and confusion

- Impaired consciousness

- Acute cerebrovascular events e.g. stroke or encephalopathy, myopathy/neuropathy and hypoxia (lack of oxygen to the brain)

- Delirium that may persist

- Dysarthria – changes to the clarity of your speech

- Dysphasia – changes to your ability to find words, form sentences, read or write

- Dyspraxia – changes to how your brain sends messages to your mouth to form sounds or words

- Dysphonia – changes to voice (see above)

- Cognitive-communication disorders e.g. changes to memory or planning

Things you can try:

- Speak slowly and with increased effort if your speech is not clear

- Try other methods if speaking is challenging e.g. writing it down, gesture

- Try to maintain a routine to reduce unexpected conversations if needed

- Look after your voice following the advice (page 18)

- Ask for help from your household with remembering information if needed

- If you are experiencing fatigue, try to limit effortful communication. This can be supported by routine, a familiar person who will know your wants/needs and using alternative methods of communication where possible

This advice has been adapted from a publication produced by the British Laryngological Association in May 2020 and a publication produced by the Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists in May 2020.

Social life and hobbies

When you have been ill, you may feel different, and you might not want to do the things you used to enjoy. You may not feel like seeing lots of people at the same time, and you might find it hard to concentrate to read or watch television.

As you recover, your concentration will get better, and your memory will improve. Try to find activities that you enjoy doing while you recover; this might include starting a new hobby or finding different ways to continue with old hobbies.

It is important that you have a balance of ‘work, rest and play’. Try to make sure that each day you can do a good balance of ‘work, rest and play’ allowing yourself time to do things you enjoy, as well as the things you have to do.

Returning to work with Long COVID

If you have a job to return to and wish to return to that job, early discussions with your workplace manager and occupational health department are often a good idea. This will help your employer to develop a better understanding of your ongoing symptoms and manageable daily activity.

To support a successful return to work it is often helpful to have a flexible and phased return. This might include altered hours or altered duties. These adjustments to your work will aim to help you to manage your symptoms during your recovery.

Before returning to work it is important to think about the physical and cognitive demands. ‘Cognitive demands’ means the thinking skills required for your job. Examples might include attention, problem solving or organisation.

These skills should be compared to how much you can manage at home. Ideally the amount you can do at home should start to match the amount you need to do at work. It can be helpful to get some ‘feedback’ on your current abilities. This is beneficial as you may have been out of work for some time and may not be aware of how tired or unfit you are.

Through doing some normal day to day activities at home, you can begin to understand your current abilities.

Examples of activities to try (providing this is safe):

- Sorting through paperwork, and letters.

- Placing books or CDs in alphabetical order.

- Using your computer for email, research, or social media.

- Walking (how long and far will depend on your current abilities and symptoms).

- Helping with a mini-DIY project (do not use ladders or sharp tools).

- Making phone calls, e.g. to the bank, a local shop, ordering a family takeaway.

- Cooking yourself a meal/snack (if it is safe to do so).

Many of these activities need similar skills and abilities that you will need to have for returning to work. For example, using your home computer for emails and social media can help you to build up your typing skills and concentration.

Now consider:

- How are you managing with these tasks?

- What went well?

- Did you struggle with anything?

- Is there anything that you need to practice?

The more information that you have about how you find different activities at home will help to inform you when you will be ready to return to work. This information can also help you to structure your return to work and understand any changes that you might need when you are at work. This will ensure a successful return to your job. Your GP can discuss any changes that you may need to return to work, as well as your local COVID Rehabilitation Team.

Getting Support at Home

Support from social services

If you require assistance with activities of daily living, you can contact your local authority for a community care assessment. A care needs assessment will be conducted to assess your requirements. The assessment will look at your limitations, difficulties and current support.

The assessment criteria have four levels (low, moderate, substantial and critical). People with substantial and critical are most likely to get support. Those needing assistance with personal care are likely to be put into either of these levels. These services are means tested. Disability living allowance, personal independent payments and attendance allowance are often taken into account as part of the financial assessment.

Attendance Allowance

Helps with extra costs if you have a disability severe enough that you require someone to help you. To find out more information and to apply go to www.gov.uk

Personal Independence Payment (PIP)

PIP helps you with some of the extra costs if you have a long-term ill health or disability. It has replaced the disability living allowance. To apply you need to call the department of Work and Pensions. For more information and the number to call go to www.gov.uk

Council tax reductions/housing benefits

If you are on low income you may be entitled to council tax support. For more information go to www.gov.uk

Winter Fuel Payment

If you are elderly you could qualify for winter fuel payment. This is money to help pay for your heating bills. For more information go to www.gov.uk

Blue Badge

Blue badges help people with disabilities or long-term health conditions, park closer to their destination. You have to fit certain eligibility criteria. For more information please go to www.gov.uk

Citizen’s Advice

For help on applying for benefits and further help please contact citizens advice for further information on what benefits you are entitled to and how to apply.

www.citizensadvice.org.uk

Smoking and COVID-19

Smoking tobacco products increase your risk of infection due to the harm caused to your immune system and lungs

- Smoking is linked with poorer outcomes in COVID-19

- It’s never too late to stop

- By stopping you can see benefits within 24 hours.

For further support and advice contact your GP, call the One You Surrey-Quit Smoking Service on 01737 652168 or email hello@oneyousurrey.org.uk or more information can be found at https://www.nhs.uk/better-health/quit-smoking/

Physical activity advice following COVID-19

Spending time in hospital or being ill at home with COVID-19 can result in a significant

reduction in muscle strength, particularly in your legs. This can be for a number of reasons, but mainly due to inactivity.

It’s not harmful to get out of breath when doing physical activity, this is a normal response.

However, if you are too breathless to speak, slow down until your breathing improves.

Try not to get so breathless that you have to stop immediately

Remember to pace your activities.

Do not overdo it – try to increase your activity levels slowly

Try to use the breathing techniques talked about at the beginning of this booklet to help control your breathing whilst you exercise. You may require a referral to a physiotherapist or the Pulmonary Rehabilitation team.

Long COVID support for patients & families

Asthma UK and The British Lung Foundation have set up a support hub to provide information and dedicated support for people who have been diagnosed with COVID-19 and their family members. This can be accessed at: www.post-covid.org.uk

Useful Websites

- The Samaritans: www.samaritans.org

- Support group for: www.icusteps.org

- The British Lung Foundation: www.blf.org.uk/

- Talking Therapy at: mindmatters.surrey@sabp.nhs.uk

- Information and support for mental health: www.mind.org.uk

- Access to online CBT therapy www.iesohealth.com/surrey

Association of Chartered Physiotherapists in Respiratory Care – Leaflets

- How To Cope with Being Short of Breath – Breathing Exercises

- How to Cope with Being Short Of Breath – Positions

- Secretion Clearance: The Active Cycle of Breathing Techniques

- Energy Conservation

https://www.acprc.org.uk/publications/patient-information-leaflets/

References

- The British Lung Foundation (2020) https://www.blf.org.uk/

- The Royal Brompton and Harefield NHS Foundation trust, Pulmonary Rehabilitation Department. (2020)

- www.nhs.uk/conditions/bronchiectasis

- The Association of Chartered Physiotherapists in Respiratory Care www.acprc.org.uk

- Homerton University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust www.homerton.nhs.uk

First Community provides front-line NHS community healthcare services in east Surrey and parts of West Sussex.

We provide first-rate care, through our first-rate people, offering first-rate value. For more information visit: www.firstcommunityhealthcare.co.uk

If you would like this information in another format, for example large print or easy read, or if you need help communicating with us:

First Community (Head Office)

Call: 01737 775450 Email: fchc.enquiries@nhs.net Text: 07814 639034

Address: First Community Health and Care, Orchard House, Unit 8a, Orchard Business Centre, Bonehurst Road, Redhill RH1 5EL

- Twitter: @1stchatter

- Facebook: @firstcommunityhcNHS

- Instagram: firstcommunityhealthandcare

- LinkedIn: www.linkedin.com/company/first-community-health-&-care-c-i-c-/

- TikTok: www.tiktok.com/discover/first-community-health-and-care

To print this page, please select accessibility tools and the print this page icon.

For office use only: Version 3 PFD_LTC034 Published June 2023